38th anniversary of the Chernobyl disaster: how Kyiv lived in the first days after the accident

On April 26, 1986, an accident occurred at the Chernobyl NPP, which became one of the most terrible nuclear disasters in history. Its consequences were felt not only by the residents of Ukraine, but also by neighboring countries.

During the first days after the accident, the people of Kyiv did not know what had happened. The Soviet authorities hid all the information.

Saturday, April 26, was an ordinary day in the capital. People went for walks to breathe in the “fresh air”, because that day was quite hot – the air temperature rose to +20 degrees. No one guessed that the city was under intense radiation.

The first rumours

April 27, 1986 was also an ordinary day. Kyiv NSC Olimpiyskiy, then known as the Republican Stadium, was bursting at the seams. More than 80,000 fans, like a raging sea, filled the stands to witness the epic battle between Dynamo Kyiv and Spartak Moscow.

The next day, anxiety gripped Kyiv. Rumors, like shadows, floated through the streets, whispered in the subway, penetrated into every home.

“Something happened”, “Explosion”, “Radiation”… No one could confirm anything, but fear had already settled in hearts of Kyivans.

From the first hours after the disaster, Kyivans were involved in liquidation of the consequences. The first victims were already being taken to the Zhulyani airport to be sent to Moscow.

The authorities were still silent…

Life still went on as usual. Shops, theaters, restaurants and cafes were open, classes were held in schools. In the evenings, Kyiv yards hummed with the laughter and noise of children.

Until April 29, no one rushed to the stations. Trains left half-empty, vacations were still far away. On Khreschatyk, from April 27 to 29, rehearsals for the May Day demonstration were boiling. Children also took part in them.

Despite the anxiety that hung in the air, people did not yet realize the scale of the disaster. Life went on, as if in the calm before the storm.

Only on April 30, the first official notice from the Council of Ministers of the USSR appeared in the newspaper “Izvestia”. It was written briefly: “There was an accident at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant. One of the nuclear reactors is damaged. Measures are being taken to eliminate the consequences of the accident. Assistance is provided to the injured. A government commission has been created.”

Demonstration on May 1

Neither the news of the disaster nor other troubles could stop the May 1 parade. Workers' Solidarity Day is one of the most important ideological holidays of the Soviet Empire. Traditionally, it was celebrated loudly, with pompous demonstrations gathering hundreds of thousands of people.

That time, in 1986, the holiday fell on the fifth day after the terrible disaster at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant.

< p>

Despite the obvious danger of holding a mass event in a city contaminated by radiation, the Soviet authorities made a tough decision: there would be a parade. It was supposed to be a signal for the international community: “Everything is under control, nothing terrible has happened!”. The smiling faces of thousands of Kyiv residents in a photo from the city center should have been the perfect image for propaganda denying the tragedy.

Panic, fear and pleas

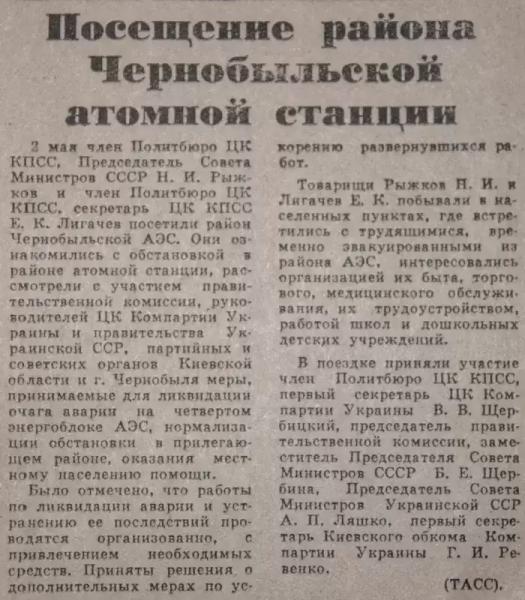

On May 2, a wave of panic once again swept through Kyiv. There were reports of a visit to Chernobyl by representatives of the highest leadership of the Union, and foreign radio stations trumpeted the terrible disaster.

Local television, trying to calm people down, broadcast the speeches of the Minister of Health of the Ukrainian SSR. He assured that nothing terrible had happened, and recommended only some “preventive measures”: wet cleaning at home, banning children from going outside, tightly closed windows.

But people did not believe. Whispers of danger lurking in the air spread through the city like wildfire.

People's anger and fear poured out on paper. Kyivans demanded the truth from the authorities. Anonymous letters and collective appeals to the leadership were full of accusations and pleas. Kyiv women-mothers begged for the evacuation of children.

Bus stations were simply jammed, people began to leave the city en masse.

Peace bicycle race

May 6, 1986 on Khreshchatyk organized the “Peace Bike Race”. This large-scale event was supposed to be another confirmation to the international community that “everything is under control”.

The organizers were counting on the mass participation of teams from friendly countries. However, apart from the French, no one risked sending their athletes to radiation-contaminated Kyiv.

The French team prudently took dosimeters with them. And the world did learn that the radiation background in Kyiv exceeded the norm by 500 times.

This news instantly spread around the city and a real panic began here. People, frightened and deceived, rushed to save themselves and their loved ones. Tickets for all trains and buses were sold out in a matter of hours, and those who did not have enough seats were ready to pay an amount equal to a month's salary for a “hare” ticket.

Leave a Reply