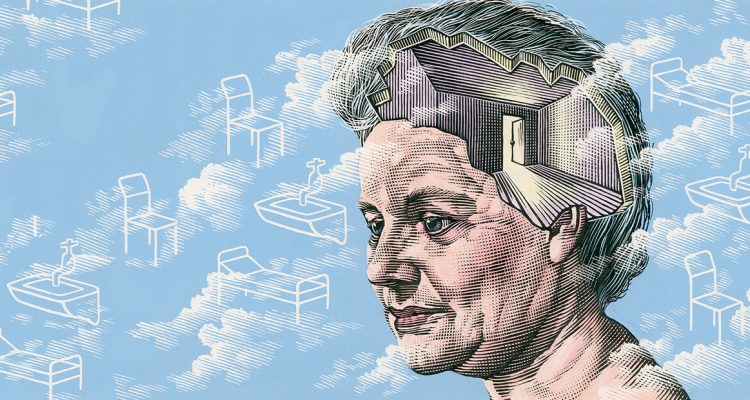

Scientists have made a breakthrough in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease

0

According to experts, by 2030 one million of Canadians will be diagnosed with dementia, or, as it is also called, Alzheimer's disease.

Despite decades of research, there is still no cure for Alzheimer's disease. But new research suggests we may have been looking at the disease the wrong way.

Researchers at Mount Sinai Hospital in Toronto suggest in a new report that Alzheimer's disease — a form of dementia — may be an autoimmune disease that, if it truth, may change how we treat disease in the future.

Until now, most research into the causes of Alzheimer's disease has focused on plaques found in patients' brains, with the theory that removing those plaques would alleviate patients' symptoms, said Ioannis Prassas, a staff scientist in the Department of Pathology at Mount Sinai Hospital and a co-author of the study. According to him, this hypothesis does not work yet.

So his team began to study another theory: that Alzheimer's may be an autoimmune disease.

This new study found specific autoantibodies — antibodies that mistakenly target the body's own tissues — in the cerebrospinal fluid of Alzheimer's patients, which Prassas said is further evidence that it may be an autoimmune disease.

“I think this further fuels this initial idea that autoimmunity may play a central role in the pathology of Alzheimer's disease,” he said.

Prassas hypothesizes that damage to the blood-brain barrier, which usually prevents the exchange of some molecules between the brain and the circulatory system, can lead to Alzheimer's disease.

“For example, we have observations that the incidence of Alzheimer's disease increases in athletes prone to traumatic brain injury,” he said. “But in any case, any damage to the blood-brain barrier can actually open the door for these immune cells to enter the brain tissue and further accelerate the destruction of certain neuronal cells, which is central to the pathology of Alzheimer's disease.”

It's just a theory at this point, but Prassas hopes researchers will study it more seriously in the future to develop new treatments for the disease.

Someday this could include giving patients drugs that change or suppress their immune systems to prevent dementia from progressing, though he said much research still needs to be done before such treatments can be prescribed.

Some in the Alzheimer's community welcome this a new approach.

“For too long, we've invested in a very narrow area or a narrow lens of dementia research, and we just haven't gone beyond that,” said Dr. Saskia Sivananthan, chief scientist at the Alzheimer's Society of Canada. “And it's time to start thinking outside the box, exploring different hypotheses that can bring dividends. So I would say I'm hopeful, and I think it's a potentially viable hypothesis.”

She noted that the likelihood of success in clinical trials for Alzheimer's treatments is very low.

“It's one of the few diseases that hasn't had a therapeutic breakthrough in more than 16 years,” said Sivananthan.

She blames this in part on a lack of funding, as Canada lags behind the rest of the G7 in funding. dementia research.

“More money is desperately needed,” Sivananthan said.

With a lot of attention on new approaches to dementia like this, and a big investment in research, she hopes that it can change.

Leave a Reply